As well as being very active in different artistic scenes LaBelle works as professor at the Art Academy – Department of Contemporary Art at the University of Bergen. I meet the Berlin-based artist in his office at the KMD building in Møllendal, Bergen. Behind us are some of the Bergen mountains, barely visible through the clouds, gloomy yet inviting.

The hope of finding an opening

Brandon LaBelles preferred form of expression is writing, he says. In a small, unsettling book Diary of an Imaginary Egyptian (2012) LaBelle has written a meditation on reaching out from a safe flat in Berlin to an imaginary Egyptian in the midst of the revolution in 2011, the Arab Spring. The book has a set of parallel stories, including one about a teenage boy named Kevin. Kevin runs away from everything, school, parents, home, friends. He is searching for something that doesn’t yet exist, an opening. “He runs with the great hope of finding nothing: an opening, a new territory, a field of love to break down all that he is.”

– Diary of an Imaginary Egyptian was a response to the intensification of social movements at that time. The Arab Spring for me still stands as a symbol for the necessity to remove the nation state as the defining form of sovereignty today, and instead, to focus on networks of solidarity. The book tries to capture this perspective by reflecting on what a revolution in Cairo means to artists in Berlin, to workers in Madison, to teenagers in Hong Kong. What the book identifies as well as celebrates are the networks of solidarity that emerged across these disparate locations. I was also led to reflect upon more personal moments, such as being a teenager in Los Angeles, and what it meant to confront the social order around me at that time. I would say, I was driven to be an artist, or driven toward the poetic imagination, as an act of escape and the desire to inhabit other worlds, LaBelle says.

A Californian punk rocker

The question of how we can get to this new place, a utopia seems to run through all of LaBelle’s work. I ask him where and what his art grew out of. In his quiet, singing voice he tells me that he in fact used to make a lot of noise, being part of the Los Angeles punk rock scene in the 1990s. LaBelle grew up in Los Angeles and went on to study art at California Institute of the Arts in Los Angeles. While studying he played drums in punk bands.

– It was at this time that sound as an art form started to interest me. This has influenced my artistic work a lot. In the 1980s art and punk music were mixing and creating an extremely experimental and hybrid form of culture. This later led to a very active experimental music scene which I became part of. There were experimental clubs and galleries, record stores and backroom gatherings, and a strong performance culture that came out of the art and punk scenes. Punk music voiced a social antagonism as well as a strong sense for building an alternative community. This influenced my friends and I, and we developed an experimental relation to noise, and in this way noise became a distinct vocabulary. Many friends around me refined techniques for working with noise, building electronics but also conceptual strategies that for me still feel extremely original.

The overlooked and underheard

– Within this scene we began to understand noise as a poetic weapon. This led me to extend my drum playing into new forms, working with objects, architectures, environments. I started to understand sound and listening as something that can link people, a way of moving bodies together, while also being rather immaterial and beyond capture. So I started to think about sound as a radical paradigm shift that could support creative forms of relationality, especially for the overlooked and underheard. What I would now call “non-communities”.

In 1992 LaBelle started a journal, Errant Bodies. LaBelle had become interested in writing and was also active in poetry journals. At California Institute of the Arts he was part of a programme focusing on experimental writing.

– At art school a very strong writing community evolved as well. New forms of hybrid writing really became more established in the 90s, between theory and fiction, art and clubs, that also related to identity politics, queer culture, LA pulp and suburban life – we should think of people such as Mike Kelley and Kathy Acker, Dennis Cooper and Amy Gerstler, not to mention Black Flag and the Angry Samoans, but also the black poets of Watts who really contributed to the emergence of rap. I started Errant Bodies while doing my BFA in ‘92, which quickly turned into an ongoing production, putting out journals as well as cassette tapes by friends.

Anti-institutional power

– I also became connected to the writing scene through Beyond Baroque, a rather ragged literary center in Venice Beach that was started by a group of beat poets and surfers in the 60s. I used to hang out there while I was in art school, bringing my activities with Errant Bodies there and sharing the journal. It was a very open situation where poets, beach bums, punks and black radicals, as well as independent academics would gather. I started to organize experimental music gigs there as well, and it became a sort of second school for me, a second home, where I learned a lot about art and life, and ideas of culture and anarchy – what it means to be on the side of radical culture, which in America is very much about lost causes and struggles made together and anti-institutional power. So it also allowed me to make these connections between sound and poetry, noise and social engagement by directly confronting real world situations.

The Imaginary Republic

From California Brandon LaBelle moved to Berlin. There he ran a project space, also called Errant Bodies. LaBelle still lives in Berlin, where he is part of a strong community of sound artists and researchers.

For a number of years now LaBelle has concentrated on projects with hopeful yet dreamlike titles such as The Imaginary Republic and Dreams of a Sovereign Citizen. The Imaginary Republic looks at how recent economic, social and political unrest have led to an intensification of grass-roots initiatives and forms of artistic activism.

– The imaginary, dreaming, labors of love, poetic constructs, these are devices I work with to approach larger social and political realities. I feel that social and political movements are often unimaginative in dealing with conflict, or understanding processes of social transformation as creative endeavors, as a question of aesthetics, of mobilizing new forms. These movements need the imagination, alongside more practical organizing, so I am very much embracing the notion of dream-work as a way to articulate and manifest ways of creating (non)community. Here I take inspiration from what Manuela Zechner calls “self-built families”. These are the families we build, the forms of kinship we create that often bypass nation-state borders and languages, not to mention institutional affiliations. These are networks of solidarity that nourish us, and that we give ourselves to. Through different artistic and collaborative activities, I feel I’m working toward creating “dreaming families”: to deploy a type of fugitive socio-materiality that may allow us to inhabit the world differently.

The logic of the night

One of the projects Brandon LaBelle did as part of Dreams of a Sovereign Citizen was titled Night Birds (take back the city). Night Birds was in LaBelle’s words an exploration of the «logic of the night», an open event attended by the artistic cultural scene in Barcelona.

– I’m very interested in the night as a particular zone or path of experience, because the night is so dramatically tied to dreaming, delirium, loneliness – as well as festivity, a kind of vague and unsteady condition that is always prone to rapture, breakdown, excess, criminality, erotic encounter. These are states for me that start to suggest another type of sociality, a queer togetherness, what I think of as “non-communities”. Non-communities are another way of thinking togetherness, which doesn’t cohere around normative identities, that in a way cannot be located and legible, but rather inhabits a state of what Kafka calls: “no fixed abode”, and which my friend Luis Guerra terms “the ilocatable”. The night is certainly an ilocatable zone – a place of disappearance that nonetheless appears, a state of community that never names itself, that doesn’t know itself as a community. The night invites us to become another type of community.

Anarchism in America

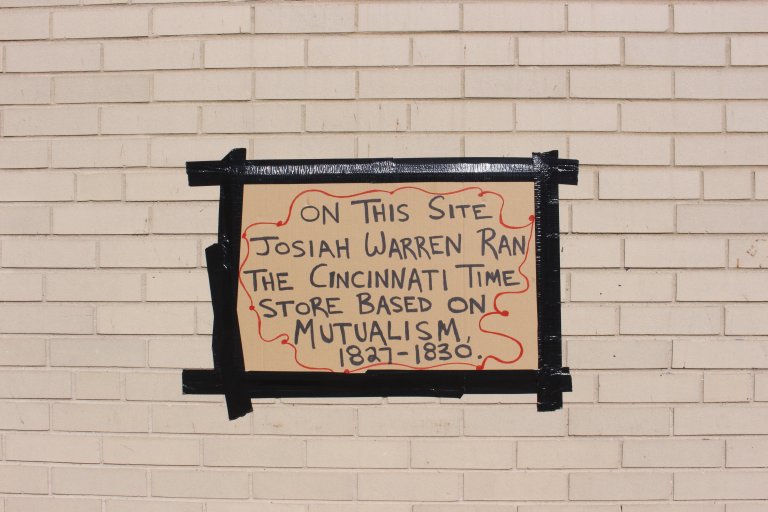

For the Dreams of a Sovereign Citizen-project LaBelle also travelled to Utopia, a small town in the United States developed by Josiah Warren (1798-1874) according to his anarchic principles about mutual aid and based on the Cincinnati Time Store.

– In Utopia I was curious what I might discover, what can we find in this lost piece of anarchic America? In the end, it is quite a forgotten place, but I was thinking to start a residency program there, occupying an old trailer home I found there. I thought, this would be a place to bring people! I also visited a number of archives where I was able to learn more about Josiah Warren, and the Time Store, which he opened in 1827.

Time is all we have

– I would be interested to also build a Time Store here at KMD, or a Time Studio, where we might enact alternative forms of not only economic exchange, but also arts education based on the topic of duration, temporality, even rhythm (back to the drums?). I think “time” and questions of daily art should be reflected upon more deeply within arts education, because artworks are essentially the result of time spent and the conditions that enable us to spend it. What does time teach us, and how do we craft time? Is it possible to create other forms of duration? Other ways of being in time, or to share time? Mierle Laderman Ukeles for me is a key artist in this regard, and how her work became a way of talking about the experiences of becoming a mother and being an artist at the same time. How these experiences shaped the way she utilized her time, how she felt time, which resulted in very compelling work. There are often discussions within the art field on questions of space and site, materiality, even labor and identity, but maybe not so much engagement with time (with a few outstanding exceptions) – even though, I would say, time is all we have.

Brandon LaBelle, The Free Scene, with Fátima Cué, Annie Pui Ling Lok, África Clúa Nieto, research action at La Tabacalera, Madrid, 2017.

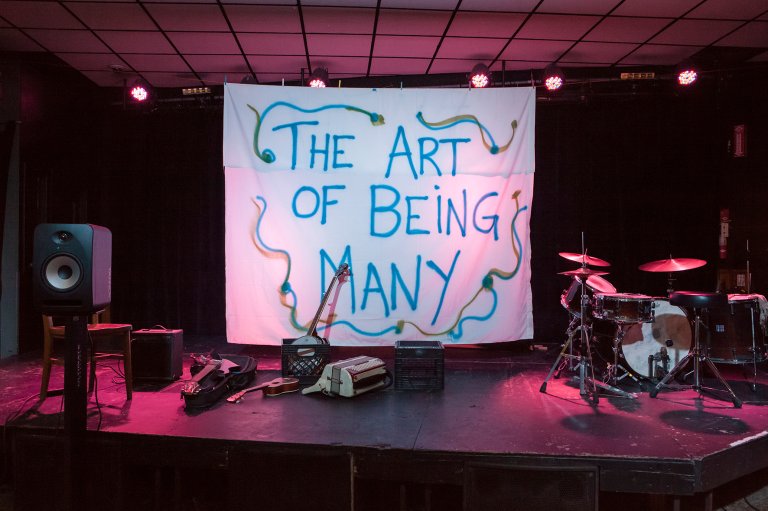

Brandon LaBelle, The Human Strike, with Marc-Antoine Cloutier, Stéphanie Letarte, Fanny Levy, and Emmanuel Delly, performance at L’Anti Bar, Quebec City, 2018.

Brandon LaBelle, In search of Josiah Warren, Utopia, Ohio, 2017.

Brandon LaBelle, The Night Birds (take back the city), secret performance, Rijeka, 2017.