Photo: Russian popsa music star, Boris Moiseev, is playing with gay references in his music.

— If you went to Russia and you thought it was homophobic, you would be shocked to see how many men and women as well, are playing with gender roles and sexuality, says Stephen Amico, who is associated professor at The Grieg Academy –Department of Music at the University of Bergen, and for many years has studied sexuality and music, mostly the Russian music scene, before lately extending his studies to the Russian population of Estonia. In Russia he has mostly studied popsa, a specific Russian type of music, which he tells is similar to popmusic though not exactly.

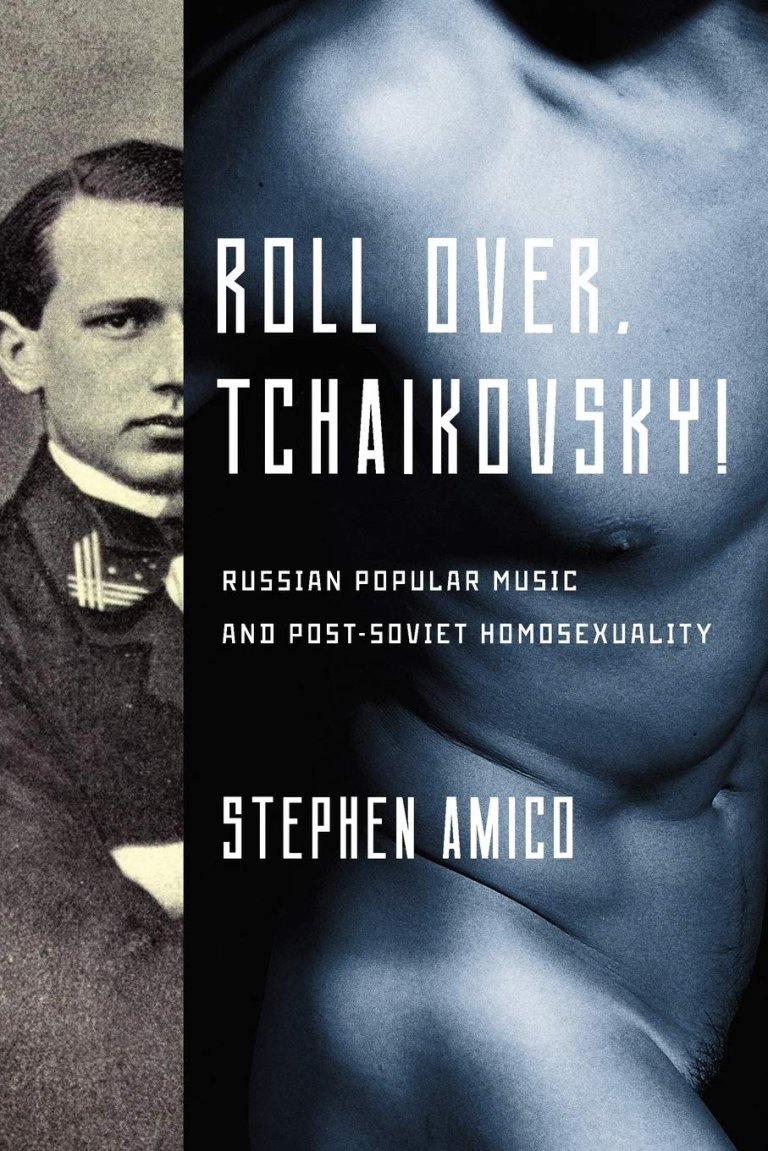

In his book Roll over Tchaikovsky! Russian Popular Music and Post-Soviet Homosexuality (2014) he uncovers how musical performances help gay Russian men create their own social spaces and selves, in relation to others with whom they share a "nontraditional orientation." (a common Russian euphamism for gay, lesbian, or queer, according to Amico).

— We don´t have equality in the West either

Amico says there are so many misconceptions about Russia in the West.

— Things are not black and white. In my research I have tried to complicate and question the idea that everything is closed and oppressive in Russia and open and tolerant in the West. It is true that the Russian state has totalitarian aspects . But if we set up dicotomy between the East and the West, and equality of the sexes, we don´t have sexual equality in the West either, he goes on to say that there are certainly differences between how sex is perceived in Russia and the West, in terms of juridicial context. But many men and women who consider their identity as protected by the law in the West, are still victims of soft discrimination, Amico says when I speak with him on mobile phone in the midst of the Corona crisis.

The musicologist says that his angle has been looking at sexual identity, not only by looking at politics, but «to explore how human sexuality is inextricably linked to embodiment and experience, including experiences of pleasure.»

He explains that one obvious way of doing this was to investigate what can we learn from human sexuality the way in interacts with music.

— We often think about sex in terms of politics, we connect it to visual culture, discourse, text, cognition. But if we leave out the body, the sensuality, the auditory, it is difficult to get a holistic understanding of how we express ourselves as sexual beings. One of the central lines in my book “Tchaikovsky, Roll over! is the uncertainty that discourse and ideology should be considered as some primary basis in the analysis of music or sexuality.

— We lack a dictionary of sex

— Often we analyze discourses and ideology precisely because we have a vocabulary to discuss these things, Amico claims, - But when we come to the question of sex - I mean sex as penetration, as smell, as touch, as taste, that is, real, material sex - it turns out that we simply do not have an accessible dictionary to which we could contact and do not seem too naive or not critical enough. Toril Moi wrote the book; What is a woman about what we can gain if we look at the bodies of women, and the bodies of men. I think that if we look at experience that might be understood outside of discourse, like that for instance of the Russian state, the people and the church, maybe we can challenge ideology, says Amico, who states that we need critical studies of the senses, of how we avoid structures that are limiting us.

The musicologist also want to challenge the western idea that LGBTQ people in Russia don´t live good lives.

— Moscow for instance have gay clubs where people line up on the street. There is so much homosexuality in Russian music, playing out this «nontraditional» sexual identity, and it is very interesting why so many performers are successful even though they represent themselves as having a ‘nontraditional orientation’.

The phantom limb of Russia

Amico says he finds the idea of the phantom limb by Maurice Merleau-Ponty useful in understanding this seemingly Russian paradox.

— It is like homosexuality is the phantom limb of Russia, as in any society, he says.

According to Amico the Soviet and Russian political structures attempted to «cut off» homosexuality from the «social body», by forbidding people to talk about it; by sending supposed «homosexuals» to the Gulag; etcetera.

— But to cut off same-sex desire isn’t possible if we accept that all people have a need for an experience of sensual, even sexual, intimacy with other members of their own sex (whether or not this is consummated via explicit sexual activity).

— So in order to explore why there are so many performers with «nontraditional orientation» specifically in music, I argued that this is not just a coincidence – in fact, both music and the phantom limb, share so many ontological attributes: they are both material AND immaterial; they are both «atemporal,» existing as something then AND now at the same time, think, for example, of listening to a song, hearing the chorus for the first time, and then, 40 seconds later, hearing the same chorus again – is it «now» or «then»?; and they are experienced both somatically/corporeally and cognitively/mentally, Amico says and adds;

— I saw a bunch of drunk of young men hugging each other the other day. Heterosexual people also need men to men, or women to women, so talking about Russia, I don´t think it is a surprise that it comes back so strongly, and highlights the fact that we need to talk about the bodies, not only the psyche.

An outlet to escape binary heterosexuality

In the article Why Homophobic Russia Loves Gender-Bending Pop Stars in The Atlantic, Amico also talks about the seemingly paradoxical way Russia loves its flamboyant and genderbending popstars and yet is extremely anti-gay. Amico says to the Atlantic that Russians in smaller cities have told him that they like the pizazz of gender-bending acts, which seem to brighten an otherwise dreary provincial existence. According to Amico older women in particular seem to love Boris Moiseev for his emphasis on beauty and tenderness - two aspects they claim were lacking in Soviet life. Amico's personal theory though, he said to The Atlantic, is that Russians simply need an outlet «to escape the binary heterosexuality that's been imposed on them.»

Once the most liberal country

He underlines that it is absolutely true that LGBTQ in Russia face a lot of discrimination, and that they might feel safer for instance in Norway. But the Russian government, was not always anti-gay.

— In the early years after the revolution, it was one of the most liberal places in the world, the legislation against homosexuality was removed, and it was not criminalised. It was with Stalin they were criminalized, and there were prosecutions of thousands of allegedly homosexual people, many arrested and charged for homosexuality, often just as a cover-up for arresting alleged enemies of the regime.

One last question. How come Russia has become your main area of academic interest?

— The short story is that I was very fond of Russian ligurgical music, I was also interested in modernist music from the 20th century, and when I took my Ph.d. in etnomusicology I discovered there was so little research on Russian music from a Western perspective. It was difficult to learn the language, but I did break through it, end it has been so enriching getting to know and love Russia.

— For me sadly it has become increasingly difficult to go to Russia, and even obtain a visa. In October, Carine Clément, a French sociologist , who was going to give a lecture on the Yellow Wests was turned away from Russia, and not allowed back for ten years. I find this very sad, I miss Russia a lot, and have had much of my academic career centering around gender and music in St Petersburg and Moscow. I have now turned some of my research to the Russian population in Estonia, Amico says.